Did my kid get trauma? How to support a kid with ACE (Adverse Childhood Experience)

I work with clients who have experienced trauma in my daily practice. I was recently asked whether their children might also experience trauma, particularly when a client has left an abusive relationship with a partner, lost someone and other stressful situations.

To address this question, here is the definition of ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences):

“Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are stressful or traumatic events, including abuse and neglect, and a range of household dysfunctions that occur during childhood which can disrupt healthy development and have long-term effects on health and behavior.”

— Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2024)

According to the original CDC–Kaiser Permanente ACE Study (Felitti et al., 1998), ACEs are grouped into three main types:

Abuse – physical, emotional, or sexual

Neglect – physical or emotional

Household dysfunction – such as domestic violence, parental substance abuse, incarceration, mental illness, or divorce/separation

What are the details of ACE?

Here is the list of ACE events:

Emotional abuse

Physical abuse

Sexual abuse

Emotional neglect

Physical neglect

Mother treated violently

Household substance abuse

Being homeless

Household mental illness

Parental separation /divorce

Incarcerated family member

Bullying

Witness violence

Witness sibling being abused

Racism/sexism/discrimination

Natural disaster / war

How does ACE impact kids?

ACEs have been linked to:

Chronic health conditions (heart disease, diabetes)

Mental health problems (depression, anxiety, PTSD)

Substance misuse

Difficulties in relationships and employment

(CDC, 2024; Hughes et al., 2017)

How does ACE affect and can damage the developing brain in childhood and adolescence? I found some articles to argue the risk of damaging their brain as well.

A child’s brain is not fully developed at birth — it is shaped by experience.

Positive experiences (nurturing, safety, play) strengthen healthy brain pathways.

Negative or traumatic experiences (violence, neglect, fear) create toxic stress that disrupts normal brain growth and wiring.

The brain “uses or loses” neural connections based on what the child repeatedly experiences.

— (Perry, 2009; Shonkoff et al., 2012)

Continuing stressful situation:

When a child faces chronic fear or neglect, their body releases stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline over long periods.

This constant “fight, flight, or freeze” state becomes toxic stress — harmful because the child cannot return to a calm, safe state.

3. Brain Areas Affected by ACEs

Damaging their behavioural and emotional functions:

Because of these changes, children exposed to ACEs often show:

Emotional dysregulation (anger outbursts, anxiety, or withdrawal)

Attention and learning problems (can’t concentrate at school)

Hypervigilance (always on guard, even in safe environments)

Impulsive or risk-taking behaviour

Difficulty trusting others or forming relationships

These are adaptive survival responses, not deliberate “bad behaviour.” The child’s brain is wired for protection, not calm learning. I sometimes get referrals through schools or their parents. However, when I meet a child/adolescent who has anger issues, some of them have ACE, and that is the outcome of brain damage.

In addition, there is some risk of neurodevelopmental disorders.

Children exposed to Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), such as abuse, neglect, or household dysfunction, are at a significantly higher risk of developing neurodevelopmental disorders, including ADHD, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), and learning disabilities. Research indicates that the cumulative effect of multiple ACEs amplifies this risk (University of Iowa Health Care, 2023).

Moreover, children with intellectual disabilities (ID) or borderline intellectual functioning (BIF) are more likely to have experienced ACEs than typically developing peers. A scoping review found that 81.7% of children with ID and 92.3% with BIF had experienced at least one ACE, with emotional neglect and household dysfunction being the most common (Browne et al., 2023).

There is also evidence of a bidirectional relationship between neurodevelopmental disabilities and ACEs. Children with existing developmental disabilities may be more vulnerable to adversities, which can further exacerbate their developmental challenges (Lundström et al., 2022).

ACEs can affect cognitive and emotional development, including difficulties with self-regulation, academic skills, speech and language, and emotional control. Prenatal and early childhood adversity, such as exposure to parental substance use or maltreatment, has been linked to these outcomes (Norman et al., 2023).

If unaddressed, early brain changes can increase the risk of:

Mental health disorders (PTSD, depression, anxiety)

Substance misuse

Chronic health conditions (heart disease, obesity, diabetes)

Relationship and attachment difficulties

Healing from ACE:

However, there is a possibility for healing because our brains have neuroplasticity, which is the ability to rewire and recover through safe, stable relationships, therapy, and social support. Through my research and work experience, I assist my clients in developing resilience and self-awareness to enhance their capacity to recover from ACEs. I have also observed the importance of fostering a sense of connection between the body and mind, especially in children, as some can feel overwhelmed when their bodies react without a conscious sense of connection to their minds.Not all children express their distressed moments with their ability, capacity, fear, confusion and self-blaming. How can we adults identify ACE?

How to identify the warning signs?

Here are warning signs.

Emotional & Psychological Signs:

Persistent sadness, anxiety, or fearfulness

Sudden mood swings or emotional outbursts

Withdrawal from friends or activities they used to enjoy

Low self-esteem or feelings of worthlessness

Overly compliant or "too good" behaviour (trying to avoid conflict)

Behavioural Signs:

Aggression, bullying, or frequent fights

Acting out in class, defiance toward authority

Risk-taking or attention-seeking behaviour

Regression (e.g., bedwetting, thumb sucking, clinginess)

Overly mature behaviour (e.g., acting like a caretaker)

Social Signs:

Difficulty forming or maintaining friendships

Distrust of adults or fear of going home

Isolating themselves or becoming “invisible”

Difficulty reading social cues or showing empathy

Physical Signs:

Unexplained bruises, burns, or injuries

Frequent headaches, stomachaches, or fatigue

Changes in eating or sleeping patterns

Poor hygiene or consistently dirty clothes

Developmental delays or frequent school absences

Cognitive/School-Related Signs:

Trouble concentrating or learning

Decline in school performance

Daydreaming or “zoning out” frequently

Forgetfulness or difficulty following instructions

What do children need from their parents?

Children need a bond with their father. Being smaller and more vulnerable than adults, children perceive the world differently and require security. When they experience a strong bond with their father, they feel safe, which supports their sense of a “safe world.”

Children also need attachment from their mother. Since their brains are still developing, they often process experiences emotionally rather than logically. For example, when they learn that their parents are divorcing, they may interpret the situation through their emotional brain, sometimes blaming themselves: “My parents are divorcing because I am a bad child.”

However, parents can provide both attachment and bond regardless of gender. I often provide parenting tools for solo parents or gender-diverse parents, emphasizing that children primarily need attachment and bond, not a specific gender.

Children respond to trauma differently than adults. For instance, after sexual assault, many children display two common responses:

Self-blame: “It was my fault” or “I am a bad child.”

Trust or affection toward the perpetrator: “They are a nice person” or “I should love them.”

These responses occur because children lack the life experience and cognitive development to understand situations logically or legally. I have worked as a child therapist since 1998, and I have seen countless children respond in these ways.

A client recently asked how they could prevent passing generational trauma—such as separation or domestic violence—to their children. I believe that vulnerable children can be protected from the further impact of ACEs by receiving consistent attachment and care from their parents. When children feel safe and secure, even in the midst of hardship, they are better able to heal and thrive.

Attachment theory:

Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969; Ainsworth, 1978) explains how a child’s bond with their primary caregiver shapes emotional and social development.

Secure attachment forms when caregivers are responsive, consistent, and nurturing.

Insecure attachment (avoidant, ambivalent, or disorganised) develops when caregivers are neglectful, inconsistent, or frightening.

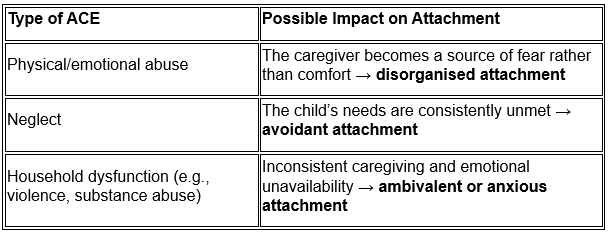

Impact of ACEs on Attachment:

ACEs often disrupt the formation of secure attachment because they involve environments of chronic stress, fear, or instability — exactly the conditions that prevent a child from feeling safe.

When a child notices that their parents do not provide a secure attachment, they often try to regulate their emotions by suppressing them. Their sense of boundaries can also become damaged and unstable. Some children may develop either overly rigid or overly loose boundaries with others, depending on the situation and the severity of the trauma.How do ACE and attachment affect the developing brain?According to Schore (2001) and Perry (2009),

Early trauma increases stress hormones (cortisol), over-activating the amygdala (fear centre).

Secure attachment usually helps regulate stress responses through co-regulation.

When attachment is disrupted, the child’s ability to self-regulate emotions and behaviour weakens, increasing vulnerability to anxiety, depression, and relationship difficulties later in life.

How do ACE and insecure attachment affect their adulthood? There is some risk of getting this impact.

Emotional dysregulation

Difficulty trusting others or forming relationships

Higher risk for mental health issues (PTSD, depression, substance misuse)

Intergenerational transmission of trauma — repeating the same attachment patterns as parents

What you can do as their parent:

So, how can we protect children and help prevent these impacts from affecting their adulthood?

The best approach is to seek professional support from trauma specialists and medical professionals. However, as a parent, there are many ways to support children beyond clinical treatment.

It is extremely important to get professional support. In addition, parents should not be kids’ therapist for safety reasons.

Therapy: Trauma-focused therapies (e.g., TF-CBT, EMDR, play therapy) can help process ACEs.

School support: Work with teachers and counselors to provide accommodations or social-emotional learning.

Healthcare providers: Pediatricians or child psychologists can monitor emotional and physical development.

Create a Safe and Predictable Environment

As I explained above, a kid needs a sense of safety and security in their daily life.

Physical safety: Ensure the child’s basic needs are consistently met—food, shelter, sleep, healthcare.

Emotional safety: Respond calmly and consistently. Avoid harsh punishments that can trigger trauma responses.

Predictability: Maintain routines for meals, bedtime, school, and activities. Predictable schedules reduce stress and anxiety.

Build Trusting Relationships

It is important for the kids to trust you as their parents because they do not know how to trust others with the unstable situation. They may not be able to trust themselves as well.

Be available: Spend quality time with your child. Even small, consistent interactions help.

Active listening: Show genuine interest in what they say. Validate their feelings (“I can see why you’d feel that way”).

Consistency: Follow through on promises; reliability helps rebuild trust in adults.

Encourage Emotional Expression

It is best to address their emotions each time. So, they feel a sense of control even though they cannot control or change the situation.

Label emotions: Help the child name what they feel (angry, sad, scared).

Provide safe outlets: Drawing, journaling, music, or play can help them process emotions.

Model coping: Demonstrate healthy ways of managing stress (deep breathing, talking, physical activity).

Support Self-Regulation

Because of their age and lack of ability, it is extremely hard to regulate their emotions.

Teach coping skills: Simple strategies like counting, breathing exercises, or grounding techniques.

Recognize triggers: Notice what situations cause distress and plan ways to reduce or manage them.

Offer choices: Giving age-appropriate choices helps the child feel a sense of control.

Strengthen Social Support

It depends on the kid’s age and developmental stage. However, social support is a very important part to sustain their well-being.

Encourage friendships: Supervised playdates or group activities can build social skills.

Seek mentors: Positive adults, teachers, or coaches can offer additional support.

Family support: Siblings or extended family involvement can help reinforce secure attachment.

Focus on Strengths and Resilience

Kids need strengths and resilience to overcome the ACE to prevent having future impact.

Celebrate achievements: Small successes reinforce self-esteem.

Encourage hobbies: Activities where the child can excel boost confidence and joy.

Reinforce coping skills: Recognize when they use healthy coping strategies.

Parenting a child with trauma can be challenging. Ensure you have your own support system to stay emotionally regulated. Children often mirror adult stress, so parental well-being matters.

In addition, you may have your ACE and never notice. Some of them get it called unhealed attachment disorder as well. Some of my adult clients found their unhealed attachment trauma when they met me.

Unhealed Attachment Disorder:

The term unhealed attachment disorder refers to the enduring effects of early attachment trauma that remain unresolved into adulthood (Bozeman Counseling Center, 2023). Attachment theory, pioneered by Bowlby, emphasizes that early relationships with caregivers form the foundation for emotional and social development (American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry [AACAP], 2023). When these early bonds are disrupted due to neglect, abuse, or emotional unavailability, it can lead to attachment difficulties later in life (AACAP, 2023).

Manifestations of Unhealed Attachment Trauma:

Unhealed attachment trauma can present in multiple ways, including:

Hyper-vigilance and intrusive thoughts: Individuals may remain in a constant state of alertness, worrying excessively or experiencing flashbacks (Bozeman Counseling Center, 2023).

Guilt, shame, and low stress tolerance: Persistent feelings of inadequacy and difficulties managing stress are common (Bozeman Counseling Center, 2023).

Dissociation and withdrawal: Emotional numbing or detachment may occur as coping mechanisms (Bozeman Counseling Center, 2023).

Chronic physical and psychological symptoms: These can include fatigue, sleep disturbances, and unexplained bodily pain (Bozeman Counseling Center, 2023).

Difficulty in relationships: Challenges in forming and maintaining close relationships due to trust issues are frequent (Schwartz, 2023).

How to be healed from the unhealed attachment trauma?:

Healing from unhealed attachment trauma often requires professional support. Trauma-informed therapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), can be effective (Mission Connection Healthcare, 2023). Working with a mental health professional experienced in attachment-based trauma is essential for addressing these deep-seated issues (Mission Connection Healthcare, 2023).

Hana Counselling offers EMDR, TF-CBT, dance movement therapy, and creative art therapy, and provides guidance to parents on using these tools. As a director, therapist, and researcher, I believe adults can meaningfully support and protect children who have experienced ACEs in many different ways.

Reference

Browne, J., Gray, K., & Smith, L. (2023). The range and impact of adverse and positive childhood experiences on psychosocial outcomes in children with intellectual disabilities: A scoping review. MDPI Nursing, 5(2), 55. https://www.mdpi.com/2673-7272/5/2/55

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, May 13). About adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/fastfact.html

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., Jones, L., & Dunne, M. P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 2(8), e356–e366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4

Lundström, S., Reichenberg, A., Anckarsäter, H., & Bölte, S. (2022). Implications of neurodevelopmental conditions and adverse childhood experiences on child health outcomes. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 10, Article 9908716. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9908716/

Norman, R. E., Byambaa, M., De, R., Butchart, A., Scott, J., & Vos, T. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences and neurodevelopmental disorders: A review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, Article 10101169. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10101169/

Perry, B. D. (2009). Examining child maltreatment through a neurodevelopmental lens: Clinical applications of the neurosequential model of therapeutics. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14(4), 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020903004350

Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., Siegel, B. S., Dobbins, M. I., Earls, M. F., McGuinn, L., Pascoe, J., & Wood, D. L. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2663

Teicher, M. H., & Samson, J. A. (2016). Annual research review: Enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(3), 241–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12507

University of Iowa Health Care. (2023). Childhood adversity may increase the risk of neurodevelopmental conditions, including ADHD. https://uihc.org/childrens/news/childhood-adversity-may-increase-risk-neurodevelopmental-conditions-including-adhd