Why DV Perpetrators Are Often Perceived as “Trustworthy”- A Neuropsychological and Social Perspective

One of the most damaging aspects of domestic violence is that perpetrators are frequently perceived by others as reasonable, credible, and trustworthy. This is not accidental.

1. Selective Self-Regulation and Social Performance

Many DV perpetrators demonstrate intact or highly developed self-control in public and professional settings.

Neuropsychologically, this reflects selective regulation rather than an absence of control:

Emotional dysregulation is expressed in private, intimate relationships

In public, prefrontal control is activated to maintain a socially acceptable persona

This allows perpetrators to:

Appear calm, articulate, and rational

Present coherent narratives in legal or professional contexts

Contrast themselves with victims who may appear emotionally dysregulated due to trauma

Importantly, this is not a lack of control, but context-dependent control.

2. Trauma-Based Inversion: “I Am the Victim”

Some perpetrators exhibit chronic amygdala hyperactivation, leading to distorted threat perception. As a result:

Neutral boundaries feel like attacks

Accountability feels threatening or humiliating

Defensive aggression is cognitively reframed as self-protection

This produces the commonly observed phenomenon in DV cases:

The perpetrator sincerely experiences themselves as the victim.

This does not absolve responsibility; it explains why their narrative can appear internally consistent and emotionally convincing.

3. Narrative Control and Cognitive Dominance

DV perpetrators often engage in narrative management:

Preemptively framing the victim as unstable or manipulative

Positioning themselves as calm, concerned, and cooperative

Using professional or legal language strategically

From a cognitive standpoint, this reflects dominance in meaning-making, not truthfulness. Victims’ trauma responses (fragmented memory, emotional reactivity) can be misread as unreliability.

4. Social Biases That Protect Perpetrators

Perpetrators benefit from systemic and cognitive biases, including:

Calm = credible

Emotional = irrational

Gendered expectations around anger and authority

Institutional discomfort with complexity and ambiguity

These biases, combined with deliberate self-presentation, reinforce perceived trustworthiness.

5. Trustworthiness as a Tool of Coercive Control

Social trust is not incidental—it is instrumental. By being perceived as trustworthy, perpetrators:

Isolate victims

Undermine disclosures

Maintain power across legal, medical, and social systems

Perceived credibility becomes an extension of coercive control.

6. How to Recognize If Your Partner Is Abusing You

Understanding why DV perpetrators appear credible is essential. Without this lens, victims may be blamed or dismissed. Here’s how abuse can be identified, even when the perpetrator seems trustworthy.

Emotional and Psychological Abuse

Emotional abuse often includes patterns that:

Undermine confidence and self-worth

Make you doubt your perceptions or memories

Create fear, anxiety, or hypervigilance

Isolate you from friends, family, or support

Gaslighting is a particularly insidious form of emotional abuse.

Gaslighting: Behaviors to Watch

Gaslighting manipulates your perception of reality. Examples include:

Denying or minimizing abusive actions: “I never did that,” or “You’re overreacting.”

Blaming you for their behavior: “This wouldn’t have happened if you hadn’t done X.”

Distorting facts or events: “You imagined that,” or “That never happened.”

Shifting responsibility: “I’m the victim here, not you.”

Using insecurities against you: “You’re too sensitive.”

Manipulating perception of others: “Nobody will believe you.”

Repeating false narratives to control the story, including in legal or professional settings.

Other Signs of Partner Abuse

Control over time, finances, or activities

Excessive jealousy or accusations of infidelity

Threats, intimidation, or humiliation

Physical aggression or coercion

Isolation from support networks

Constant monitoring or surveillance

Manipulating others to doubt your experiences

Steps to Protect Yourself

Trust your instincts: Your feelings of unease are valid.

Document incidents: Keep factual records of words, actions, dates.

Seek professional support: Counsellors, therapists, or domestic violence services.

Build a safety plan: Trusted people, safe places, emergency contacts.

Know your rights: Legal protections exist for survivors of abuse.

Abuse is never the victim’s fault. Recognizing the signs is the first step toward regaining safety, autonomy, and peace of mind.

7. Clinical Integration: EMDR × Zen

Understanding a perpetrator’s perceived credibility also informs trauma recovery. EMDR addresses the survivor’s trauma-based dysregulation, and Zen-informed mindfulness rebuilds self-observation and nervous system coherence. Healing is not only personal—it restores the capacity to trust your own reality.

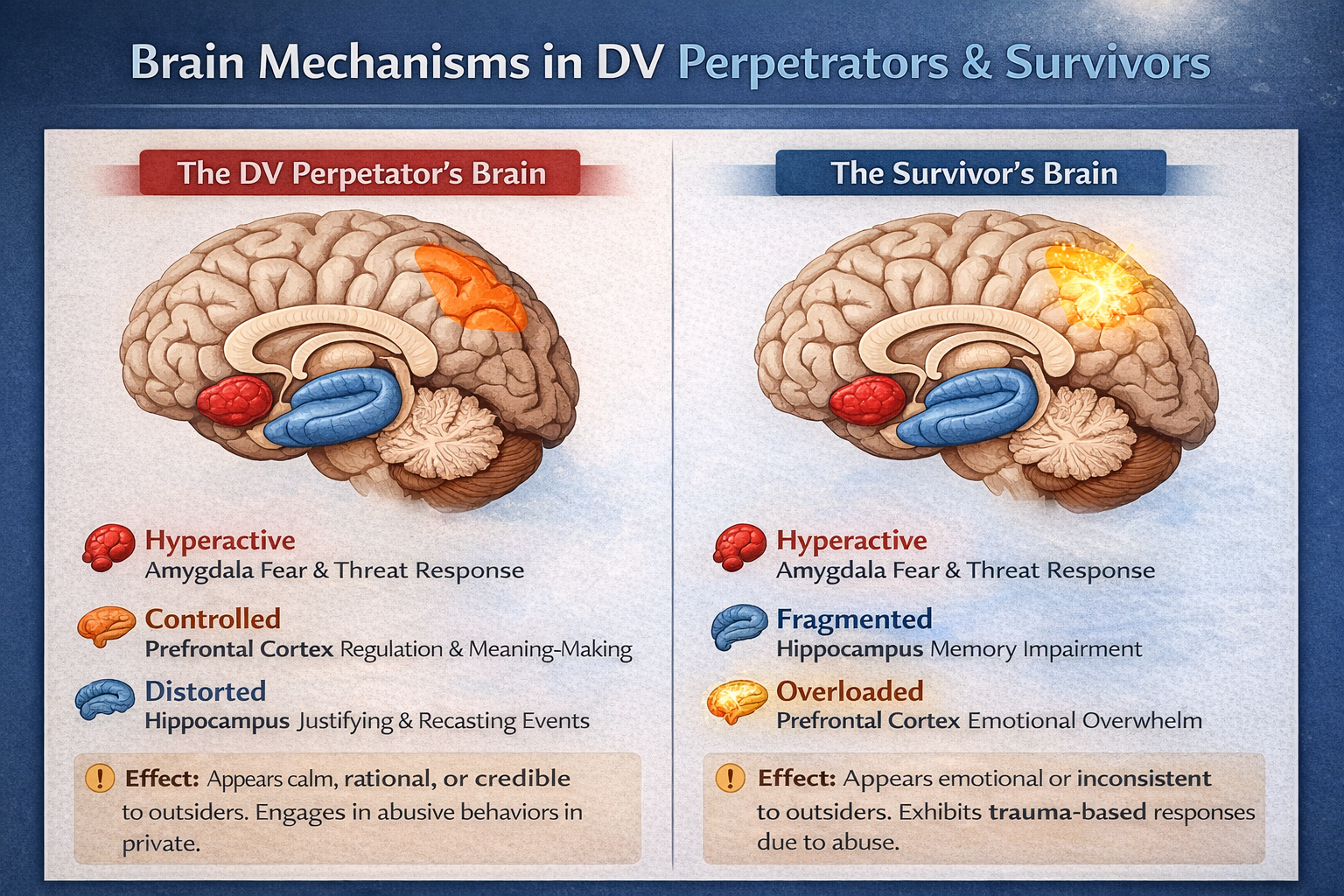

8. What Happens in the Brain of DV Perpetrators and Survivors

Neuroscience helps explain the behaviors and experiences in abusive relationships. Understanding these mechanisms clarifies why perpetrators can seem credible and why victims’ responses are often misread.

A. The DV Perpetrator’s Brain

Amygdala – Fear and Threat Response

Overactive or hypervigilant in perceived threats.

Even minor boundary-setting may trigger defensive aggression.

Prefrontal Cortex – Regulation and Meaning-Making

Can remain highly active in public or professional settings.

Allows the perpetrator to control emotions, appear calm, and craft believable narratives, even while being abusive in private.

Hippocampus – Contextual Memory

Can distort memories selectively to justify their actions or recast themselves as the victim.

Effect: This combination explains why perpetrators can present themselves as rational, calm, and trustworthy to outsiders, while simultaneously engaging in coercive or abusive behaviors in private.

B. The Survivor’s Brain

Amygdala – Hyperactivation

Heightened fear and threat response, especially after repeated abuse.

Triggers anxiety, startle responses, and hypervigilance.

Hippocampus – Contextual Fragmentation

Stress and trauma can fragment memory.

Victims may struggle to recall events linearly, which can make them appear inconsistent in legal or social settings.

Prefrontal Cortex – Regulation Overload

Constantly working to control emotions under threat.

Cognitive resources are diverted to safety and coping, which can reduce clarity in storytelling or assertiveness.

Effect: These neural patterns can make survivors appear “emotional” or “unstable” to others, which perpetrators may exploit in courts, workplaces, or social situations.

C. Why This Matters

Understanding these brain mechanisms helps:

Explain why perpetrators appear trustworthy while victims’ credibility is questioned

Highlight that survivors’ responses are neurobiologically normal reactions to trauma

Support trauma-informed practices like EMDR and mindfulness, which aim to retrain the nervous system and restore confidence in reality perception

Empowerment and Healing: Hana Counselling Perspective

"Even after trauma, your life has meaning, and your path forward is yours to reclaim. At Hana Counselling, we guide survivors to reconnect with their ikigai—the deep sense of purpose that gives life vitality. Through Zen mindfulness, you can observe thoughts and emotions without being overwhelmed, cultivating clarity and presence. Self-compassion reminds you that your reactions are natural responses to trauma, not signs of weakness. Drawing on Naikan reflection, you can acknowledge what others have contributed to your life while recognizing your own resilience and strengths. Morita Therapy teaches acceptance of feelings without overidentifying with them, and taking purposeful action despite discomfort. Together, these approaches restore agency, calm the nervous system, and empower survivors to live with clarity, dignity, and hope."- Ai Kihara (Director at Hana counselling)

References

Bancroft, L. (2002). The Batterer as Parent

Stark, E. (2007). Coercive Control

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and Recovery

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The Developing Mind

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score